Algorithmic Trading: Pricing Derivatives

Sometimes I look back on stuff I wrote in the past and cringe, because back then I didn’t know what I know now, but hindsight is 20/20, I guess.

Algorithmic Trading

My side hustle is algorithmic trading. I have one strategy running that’s based on techniques from stat arb and another one in beta testing that is a trend follower. The fundamental idea behind trend following is that nobody can predict the future, and media attempts to explain why e.g. the S&P dropped nine points are retroactively assigning a narrative to fit the observed data. Price and price alone reigns supreme in the world of trend following. Sure, the markets /might/ have tanked because of a tweet, but the only objective truth is the market price. So with trend following the general plan is to arrive late to the party, and to overstay your welcome: When a trend has clearly been established, you hop on the bus. When the trend has clearly ended, you hop off. Conceptually, it’s as simple as that.

Why Derivatives?

I trade options rather than long shares because they offer convexity. Consider the Greeks: If you are long an out-of-the-money (OTM) option, your position will have small absolute values of delta, gamma, and vega. As the underlying moves and a long option approaches the money, all three of those greeks increase in magnitude. My hypothetical 10-delta call gains 10 cents for every move in the underlying, but then delta itself increases due to gamma, so with each $1 gain in the underlying, my long call’s value accelerates nonlinearly. This is convexity, and the reason it’s good is that it offers asymmetric risk to reward ratios. If you buy a 50-cent contract then you’re only on the hook for the $50 initial outlay, but you might be able to sell that contract for several hundred dollars despite a meagre increase in the underlying instrument.

Why a pricing engine?

I trade with Interactive Brokers (IBKR). The landscape of discount brokerages in Canada really sucks, but IBKR is the sole bright spot in an otherwise dismal morass. Most of them will charge you absurd fees /just for the trade/ and then an additional per-contract fee on top of that, even for defined-risk positions. I’m looking at you, Questrade.

In any case, IBKR’s API is solid but you can tell it’s got some legacy stuff running because parts of it are a bit janky. They have several interfaces to their systems, one of which is OAuth 1.0a and as far as I can tell their auth system is just plain-ol’ not-so-subtly broken. My signatures fail to validate about 25% of the time, despite having gone over the code several times with a fine-tooth comb. Anecdotally, I’ve chatted with several other IBKR users who also experience these validate failures, so the only conclusion is that it’s a technical problem on IBKR’s end.

Speaking of technical problems, IBKR won’t allow us to just fetch a given contract. Instead, we need to follow the following ritual:

- Search for the underlying instrument’s Contract ID (“conid”), even if you already know it, by hitting

/iserver/secdef/search - Fetch a list of strikes for options on the underlying for a particular month. These are returned as bare lists of numbers, with no accompanying info. If there are multiple expiries in a month (like for SPY, with expiries every day) then you get them all, as a list, from

/iserver/secdef/strikes - Then, we are required to search for the actual tradeable contract objects, to get the conids of the actual contracts you want to trade from

/iserver/secdef/info. You can’t request these in bulk. You have to hit the endpoint once for each strike of interest. Again, if there are multiple expiries in a month at that strike, they all just come in one big JSON array. You can filter on rights (i.e. puts vs calls) but you can’t just specify a DateTime and have them come back.

It’s my understanding that this incantation is needed to cause their servers to instantiate the options chain in memory on their end. Only after we go through that process can we actually call the /iserver/marketdata/snapshot endpoint to get a top-of-book quote. Oh but wait, if you didn’t call the /iserver/accounts endpoint first, then the market data snapshots will just silently fail forever, and this is mentioned only obliquely in the docs.

Anyways.

You can see that as a consequence of their options chain setup, you necessarily can’t get the greeks or prices for an instrument until after you get the bare list of strikes, and if you want to manage your delta exposure (which I do) then you need to be able to locate strikes based on their greeks or by their price, which means we either need to perform a binary search/bisection and make a whole bunch of API calls in the process (slow), or we can run a pricing engine locally to minimize the number of API calls we need to make (potentially faster depending on how accurate we can price things locally).

Pricing models

Black Scholes is what we were taught in my MBA finance classes, but that’s only for European-style options and isn’t accurate for American puts in particular. Additionally, the Black-Scholes model was based on assuming lognormal stock price fluctuations with a constant volatility. However, real markets exhibit fatter tails than lognormal, and the model doesn’t predict the vol smile. So when we want to predict an option’s price, what we really need to do is predict the corresponding IV. On top of that, we need to contend with American-style exercise, which increases the observed market price, especially for puts.

In the past I’ve written about how the Heston model is “my preferred model”, as if I was intricately familiar with them all. Well, stochastic volatility models like Heston’s are great because you can calibrate them once and out comes a vol surface across all strikes and expiries. That’s dope, but the calibration is rather involved, and solving 2D PDEs or running LSMC can be pretty computationally expensive depending on the size of the grid. On my (commodity) hardware I was looking at hundreds of miliseconds and even into the seconds for pricing a single American vanilla. I’m not trying to compete with HFT firms, but that’s unacceptably slow for me. What’s more, the model plus calibration routines weighed in at like 2300 lines of code. Yeah no thanks.

What we need is a model that can handle the American exercise, and is computationally-efficient.

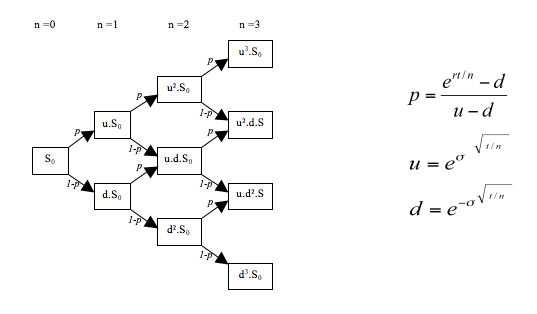

Enter the BOPM

It’s a regular binomial tree, where the value at each step is the price, and moving between steps involves multiplying by an up factor or a down factor, which take the form of exp( ±sigma^[ sqrt(t/n) ] ). The thing I like most about the binomial method is that the greeks just naturally fall out of the backward recursion, so you get them “for free”, which feels like a win. I’m running this code on a 2.4GHz Xeon from 2012 so it’s not like I’m drowning in compute. I’ll take all the performance wins I can get, thank you very much! The BOPM is essentially a discretization scheme, and I’ve implemented mine using the standard Cox-Ross-Rubenstein (CRR) method. Rather than a true local-vol model, to approximate the smile I added a parametric fit using the Merrill Lynch SVI model. My strategy only trades 1-5 DTE American vanillas, so rather than gathering a surface of IVs across multiple strikes and tenors, I just grab a half-dozen strikes straddling the money, at one single expiry, and fit an SVI curve each time I want to price, which is very fast. In C# I store the fit parameters as an immutable record and re-calibrate every hour, or if there’s a significant change in IV or a significant move in the underlying instrument.

Now, because the binomial method involves discretization, there are two key sources of errors in this model:

- Discretization error, that is error to do with the fact that we’re essentially piecewise approximating a continuous function so we necessarily can’t capture features that are finer than the resolution of our discretization scheme.

- Model error, that is error to do with how the model represents reality, bugs in the implementation, and to do with the inputs and outputs. As a prof of mine once said: /all/ models are wrong, but some of them are useful.

Key point to bear in mind: the workflow imposed by IBKR means I just need to get “close enough”, since I’m going to have to snapshot the option contract anyway, so I can confirm the greeks and current price meet my strategy requirements. Since I’m not computing a proper vol surface (like Heston would give me) it’s likely that I’m not capturing the full smile, and thus probably understating the volatility which in turn means my model will probably under-price the options relative to the market. But, critically, being a few pennies off is okay, because I have to snapshot the option contract anyways to get the current price. I’m just here to reduce the number of API calls I need to make since they’re so slow.

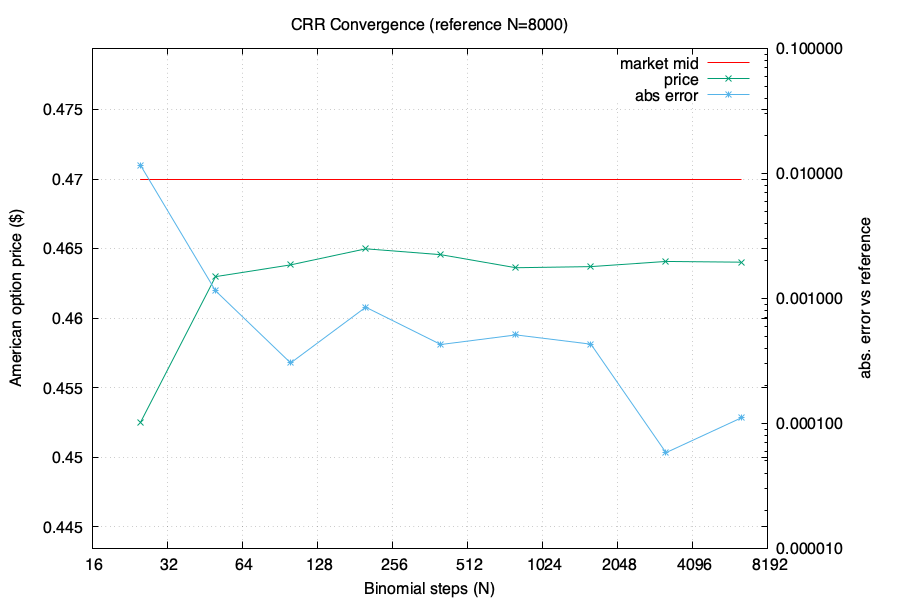

To assess the aforementioned errors we’ll take two reference points. The first is the actual market price of a particular option, and the second is the model output for a humongous tree, 8000 levels deep. The huge tree should have minimal discretization error, especially for short tenors in the sub-weekly range. If the huge tree diverges significantly from the market price, then we probably have significant model error. If the huge tree is close to the market price, then we know our model is good and we can then check the discretization error by computing a series of trees of different sizes and examining their behaviour. We should see them converge to the huge tree (and to the market), as the discretization error diminishes with increasing N. Here are the results from my implementation, for a 17 April 2025 SPY $538 call, which at the time I ran this test was sitting around 10 Δ:

On the left hand/primary y-axis is the American price, with the market-observed midpoint price in red (i.e. the mid of the bid-ask spread), and the green line representing the model’s predicted price at the number of binomial steps indicated on the x-axis. On the right hand axis, in log scale, is the error between the model and the “huge tree” with N=8000 represented by the blue line.

We can see that the discretization error (blue line) quickly drops below a penny, which is great news: That means our tree converges, and we maximize performance by choosing the smallest N that meets our accuracy requirements, and freeze that number in production. After seeing this test I chose N = 400, which on my Xeon runs in less than 100 microseconds.

Similarly, we can see that the model itself is sound, and I’m capturing the smile pretty well with my parametric SVI fit. At 10 delta we’re seeing about a half-penny price miss between the market-observed price and the model price.

Not bad for 150 lines of code!