Letting Go

tl;dr I killed my startup this year. It wasn’t an easy decision.

Background

My wife is a doctor. She’s part of a “call group” of physicians who collectively cover several different services. At the time this story takes place I believe there were 14 or 15 doctors in the group, covering about a dozen different services at three different hospitals and clinics, plus overnight and weekend on-call duty. In 2022 her group received a sales pitch/demo from a company, who I will deliberately not name, selling scheduling-as-a-service. The service was to replace their current solution of one very-stressed-out computerphobic doctor who aged prematurely every month making a schedule in Microsoft Excel assigning doctors to services, juggling vacation requests, handling colleagues trading call shifts at the last minute, etc.

In my wife’s call group this particular scheduling doctor, quote, “hated her life” every time she had to make the schedule, and thus the group was very interested in an automagic solution. The proposal they were handed was pretty standard but when my wife and I were discussing it over dinner one night, I balked at the price tag. I distinctly remember saying that the price tag was so exorbitant that it made me want to whip up a competing service and undercut them on price purely out of spite.

At the time, I was being facetious, and had no intention of actually doing it. But some ideas have a way of holding on tight, and after a few weeks I realized that I had the technical skill to build the product, and having recently got out of the military I also had the time to build it. COVID was just winding down and working from home was the new cool thing, so I dove in head-first.

Enter PRN

I called it “PRN” which stands for Pro Re Nata, pronounced (“pro ray nah-tahh”), a Latin phrase that basically means “as needed”. It’s what doctors write on medication orders so that Nursing can give meds based on the patient’s needs rather than on a fixed schedule like “20 mg infusion every 6 hours”. The name was therefore a cheeky play on that, implying that the software would help schedule physicians (and later nurses) as needed. Get it?

It turns out that assigning doctors and nurses to a specific service on a specific day is a form of “the timetabling problem” which is a very well-studied family of NP-Complete problems involving some variation on the theme of assigning a finite set of professors to teach a finite set of classes in a finite set of classrooms that are available for a limited number of (usually-overlapping) time slots. There’s even an international timetabling competition!

As a refresher, NP-complete problems:

- are decision problems (i.e. you can answer them with a yes or no)

- have solutions that are easy to verify

- have solutions that are difficult to calculate directly

- can be brute-forced

So, brute-forcing is an option and it sounds feasible for just 14 doctors, but our neighbor is an Emergency doc and his department has more than 50 doctors, and at that scale a brute force approach quickly becomes infeasible thanks to factorials. I wanted something that would scale economically, and something that would produce aesthetically-pleasing schedules subject to various constraints such as “doctors can’t be in two places at once” and nice-to-have rules such as “if you’re on [demanding service] one week then we try to put you on [light workload service] the following week”. A few days’ research into timetabling algorithms led me to:

Simulated Annealing

Have you ever taken a wire coat hanger or metal paper clip and bent it back and forth repeatedly until it stiffens up and eventually snaps? That’s called “cold working” the metal. Metal that has been cold-worked becomes harder and stronger but at the cost of reduced ductility which makes the metal more prone to breaking (brittle) rather than bending. Annealing is the process they teach you in your second-year Materials course whereby you take a metal and heat it up to a specific temperature called the “recrystallization temperature”, hold it there for a specific amount of time, and then let the metal cool at a specific rate. This more or less “undoes” the cold-working process and can usually restore the metal to its original state. I’ll spare you the details because I don’t want to dig out my metallurgy textbook but in broad terms what’s happening at the molecular level is that the metal’s internal crystal lattice structure can essentially re-organize itself into a more ordered, lower-energy state. Very cool.

Simulated Annealing takes this concept and applies it to a multidimensional solution space represented by a cost function. The cost function computes the “badness” of the proposed solution under consideration. For example for each nice-to-have goal that you fail to meet (like not giving people the vacation time off they requested) you increase the cost parameter by, say, 10. If you violate a constraint (like having one doctor in two places at once) then you increase the cost by a significant amount, say 9999.

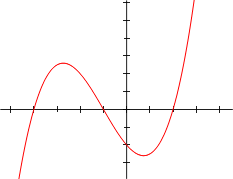

If we tried a simple gradient descent we might get caught in a local minimum. Picture for example the graph of some cubic function. We might get caught in the trough when lower-cost solutions exist elsewhere.

In Simulated Annealing, we have a hyperparameter that we call “temperature” representing the solver’s willingness to accept a worse solution. This “temperature” starts out at a high value and decreases gradually, like the real temperature of a metal cooling. This is how Simulated Annealing escapes the local minima: While the temperature is high, the solver may choose to temporarily accept a higher-cost solution, with a decreasing likelihood of this happening as the temperature decreases with each successive run. The idea is that the solver can escape being caught in local minima by passing through “bad solution space” on its way to “optimal solution space” and arrive at a much lower-cost solution in the end.

I wrote my own Simulated Annealing solver (which I plan/hope to one day have time to clean up and open-source). I opted for Common Lisp. Paul Graham of Y Combinator fame has written several essays extolling the virtue of lisp(s) and I mostly agree. Common Lisp is very expressive, so you can be very productive in it. In my not-so-humble opinion what’s mostly missing is the library ecosystem, but I digress. It took me a few months of working at night after the kids were in bed to build an MVP, and then I started shopping it around. Since my wife is a doctor I had an “in” to a lot of physician groups.

Now to actually go out and sell the thing

I started approaching my wife’s friends and colleagues. At first it was awesome. Solopreneurship can be extremely satisfying and exciting! A lot of people I talked to reported the same pain points. They had someone that “did the schedule” every X number of months and it was a hassle. They had to email that person for scheduling. They had to rely on that person to equitably settle disputes, like who is on call over Christmas or summer long weekends when nobody wants to do it. The scheduler person usually doesn’t like “doing the schedule”. Quite a few were paying for a scheduling service, but it was usually a lot of money. One group in particular was paying for a service, and then taking that service’s output and spending dozens of hours massaging what it spit out to get something workable, and that group was paying one of its doctors thousands of dollars a year to do that massaging of the schedule on everyone’s behalf. Great, I thought, as visions of dollar signs danced in my head. I can get all these people to sign up for my product because it actually works and I know half of these people socially through my wife.

In the very first lecture of my MBA program (“Intro to Competitive Strategy”) the prof went over what are called Porter’s Generic Strategies. There are three categories into which all competitive business strategy can be grouped:

- Cost Leadership, which is targeting consumers across an entire industry based on offering a lower price.

- Differentiation, which is targeting consumers across an entire industry based on offering a product with more/better features, etc.

- Focus, which some texts break down into Cost Focus and Differentiation Focus, but basically it’s either Cost Leadership or Differentiation applied to only a niche subset of an industry.

By deciding to “undercut these guys on price out of spite” I had started down the path of a Cost Leadership strategy. My value proposition was to deliver an instance of my Simulated Annealing solver with a simple web interface and importable calendar feeds, at a fraction of the cost of my competitors. I’d be making money because my overhead was so low. Value added: support was easy and accessible, because the first few customers knew my wife either directly or through someone else, they could just go “Oh it’s [Dr Wife]’s husband, just text him”. I thought this would be a no-brainer. Why pay all this money for a schedule when I can do it for you for a third of the cost?

By now we were into 2023 and ChatGPT had taken the world by storm. Everyone was touting AI-powered everything including some of my competitors. The competition had native mobile apps. They had established customer bases in the States and in Canada. They had dedicated customer acquisition pipelines, they had “Client Success Managers”.

And I was hearing, over and over again, that my product was good, but I just wasn’t able to unstick my prospects from their existing paid solutions. The conversions I did get were of the “One overworked person doing it all in Excel” kind, but those were fewer in number than I’d initially thought, and that led me to the realization that ultimately killed PRN: I was selling scheduling software, but my successful competition was selling peace of mind. The were selling the freedom to not have to worry about the schedule at all. They were offering turn-key solutions with video tutorials and dedicated account managers to get people up and running, because these doctors and nurses are all extremely busy and they’re well-paid, too. They’re paid well enough that they’d rather pay more money for a turnkey solution than pay less for PRN. My Cost Leadership strategy was getting its ass kicked because this particular segment of the market (doctors) aren’t particularly price-sensitive for this type of product, and so the most successful products were the ones pursuing a Differentiation-type strategy, offering superior features and UX.

The hardest part

Once I realized why I wasn’t finding product-market fit, I started looking at what it would take to get there. Everyone was excited by “AI”, so I did a trial of integrating ChatGPT into my service but the results weren’t better than what I was getting from my Annealing code. Often they were worse, as the early versions of ChatGPT were particularly prone to hallucinations. I realized that it would take probably several months of development time to get where I needed to be technically, and only then could I realistically start the business development side of things again.

Did I really want to be in this business? Admittedly, the early months building PRN were really, really fun, but if I was honest with myself, solving this problem just doesn’t scratch the itch. I think I was excited to be working for myself more than anything, especially after years in the military, but I don’t think the problem itself really excited me. Meanwhile I was extremely busy with my MBA and juggling parenting my 3 year old for whom we didn’t have childcare lined up, so justifying working on PRN was getting harder and harder.

And so, with PRN having never come out of beta, I let my few users know I’d be shuttering the product and in March of this year officially pulled the plug. I don’t regret spending the time on it. It was an absolutely stellar learning experience, but it’s time for something new.

The takeaway

Being able to identify your target market is not sufficient. When building a product, you really need to understand not just your customers but also your competitors. Failure to properly map out the competitive landscape is a recipe for disaster.