Zeppelins

It’s Thanksgiving here in Canada, and I was talking to someone in my family about drone-scale zeppelins, and how cool it would be to have one. Where I live it can be quite gusty at times, so we got to thinking about how windy it could get before you wouldn’t be able to fly your zeppelin drone lest it blow away into the Pacific, or the mountains.

From First Principles

In aerospace we have a handful of important dimensionless ratios that characterize important aspects of the airflow and/or the airframe. One is the aspect ratio, which is the ratio of a wing’s span to its chord, (thus units of length cancel out, making it dimensionless) and it has important effects on things like induced drag, aerodynamic efficiency, roll response, and so on. Another is the well known Reynolds number, a ratio of the inertial forces to the viscous forces in a fluid flow. A low Reynolds number indicates the flow is laminar, whereas a high value indicates the flow is turbulent. The Reynolds number (hereafter Re) affects the drag coefficient of a shape, among many other things.

In considering gust response of a zeppelin I got to thinking how we might come up with a “gust number” that would characterize the gust response of a cigar-shaped hull. As a means of illustration, suppose we wanted to compare the sustained turn performance of different fixed-wing aircraft. We might choose to take the ratio of the minimum theoretically-required drag to the maximum theoretically-required thrust, and arrive at a sort of “turning efficiency” number. So let’s examine some empirical design numbers that I think would be helpful if I was building a zeppelin (or a blimp) drone.

Practical Concerns

Prospective operators of an aerostatic drone don’t care about Re or aspect ratios. The question they need answered is “can I fly in this wind?”. So, assuming we have motors that can gimbal, do we have enough power/thrust to make headway against wind, and are we able to maintain our station-keeping ability? Let’s consider the pathological case of a prolate spheroid (i.e. shaped like an American football) hull subject to a 90-degree crosswind, that is a direct broadside gust. Let’s assume our motors are on servos and can gimbal to provide thrust in any direction. We need to know:

- Do we have enough thrust to actually push through the wind?

- How violently is the wind going to toss us around?

- How far is a gust going to cause us to drift from our original position?

Buoyancy

The upward buoyant force is just the weight of the displaced air. The downward weight is the weight of the helium (or other lifting gas like hydrogen) plus the weight of the airframe, payload, batteries, etc. At standard conditions, the density of air is 1.225 kg/m^3 and that of helium is 0.1785. So for each cubic metre of helium gives us 1.225 - 0.1785 = ~1.05 kilograms of gross mass lift at standard conditions. To get from gross to a useable payload we’d need to subtract the mass of the vehicle itself:

m_payload = ((rho_air - rho_he) * V_gas) - m_vehicle

Drag

Next we need to determine what forces a gust of velocity u will exert on our hull. Going back into my textbooks and digging around the NASA technical reports server I found some experimental wind tunnel data for cross-flow around cylinders at various values of Re, as well as some experimental data to adjust drag coefficients for prolateness efficiency. Throwing a little python at it, we can make some linear interpolaters to capture the general shape of the data:

def make_linear_interpolator(points, extrapolate="error"):

"""

Make a 1D linear interpolator.

points: list of (x, y)

extrapolate: "error", "clamp", or "linear"

"""

pts = sorted(points, key=lambda p: p[0])

xs = [p[0] for p in pts]

ys = [p[1] for p in pts]

def interp_segment(x, x1, y1, x2, y2):

if x1 == x2:

return y1

return y1 + (x - x1) * (y2 - y1) / (x2 - x1)

def handle_left(x):

if extrapolate == "error":

raise ValueError(

f"x={x} is below domain [{xs[0]}, {xs[-1]}]."

)

elif extrapolate == "clamp":

return ys[0]

elif extrapolate == "linear":

return interp_segment(x, xs[0], ys[0], xs[1], ys[1])

else:

raise ValueError(f"Unknown extrapolate mode: {extrapolate}")

def handle_right(x):

xn_1 = xs[-2]

yn_1 = ys[-2]

xn = xs[-1]

yn = ys[-1]

if extrapolate == "error":

raise ValueError(

f"x={x} is above domain [{xs[0]}, {xn}]."

)

elif extrapolate == "clamp":

return yn

elif extrapolate == "linear":

return interp_segment(x, xn_1, yn_1, xn, yn)

else:

raise ValueError(f"Unknown extrapolate mode: {extrapolate}")

def interpolator(x):

if x < xs[0]:

return handle_left(x)

if x > xs[-1]:

return handle_right(x)

# Find segment [x1, x2] with x1 <= x <= x2

for (x1, y1), (x2, y2) in zip(pts, pts[1:]):

if x1 <= x <= x2:

return interp_segment(x, x1, y1, x2, y2)

# Should not get here if points are well-formed

raise RuntimeError(f"Failed to bracket x={x} in points {pts}")

return interpolator

This lets us do something like this to get a drag coefficient:

cd_estimator = make_linear_interpolator(DRAG_POINTS, extrapolate="clamp")

cd = cd_estimator(Re)

Gust Response

Let’s assume a wind gust of u = 5.0 m/s strikes our 3-meter long by 1-meter wide prolate spheroid broadside. At standard density and viscosity the Reynolds number would be about 350000, well into the turbulent regime. This makes logical sense as the viscosity of air is quite low (on the order of 10^-5), so inertial effects will dominate. At that Re my interpolated data suggest we’d see an adjusted drag coefficient of about 0.6, with the wind imparting a force of about 23 Newtons.

Now, conceptually, if the gust lasted forever then our airship, stationary at time t=0 would gradually accelerate until it eventually reached equilibrium with the free-stream velocity of the gust u. We can model this as an ordinary differential equation (ODE):

dv/dt = k * (u - v)^2

where:

dv/dt = acceleration

k = [0.5 * rho_air * Cd * Area] / mass

u = freestream wind speed

v = speed of the airship at time t

With a little rearranging this ODE is separable, so if we integrate to get velocity as a function of time in the gust, it comes out as:

v(t) = U - [k t + 1/U]^-1

If we integrate again to get displacement as a function of time in the gust, x(t), then we can define Δx = x(t_1) - x(t_0), normalize by length L, and come up with what I called a “drift number”:

DN = Δx / L

This is a dimensionless ratio that tells us how many hull lengths that a given finite gust of wind would be expected to push us, which I think would be pretty useful to know.

Next: If we had a large zeppelin with passengers, or a drone of any sort with sensitive equipment onboard, we might want to know not just how far we’d go but how violently the wind would push us. Starting from the ODE again, the initial acceleration is always going to be the largest in magnitude, and if we assume the airship starts from rest:

a(t) = dv/dt

a(t) = k (u - v)^2

a(0) = k (u - 0)^2

a(0) = k u^2

Normalize that by gravity to get G’s, a non-dimensional ratio of an acceleration vs that of gravity, call it the Gust number G:

G = k u^2 / g

where:

k = [0.5 * rho_air * Cd * Area] / mass

u = freestream wind speed

g = acceleration due to gravity

So for example we could look at a 1.5 kg drone in that same 5 m/s wind gust, and see that after 5 seconds (a long gust!) the vehicle would be expected to reach about 4.7 m/s, an acceleration of 0.94 m/s^2 or a Gust number of roughly 0.1, nice and gentle.

Thrust

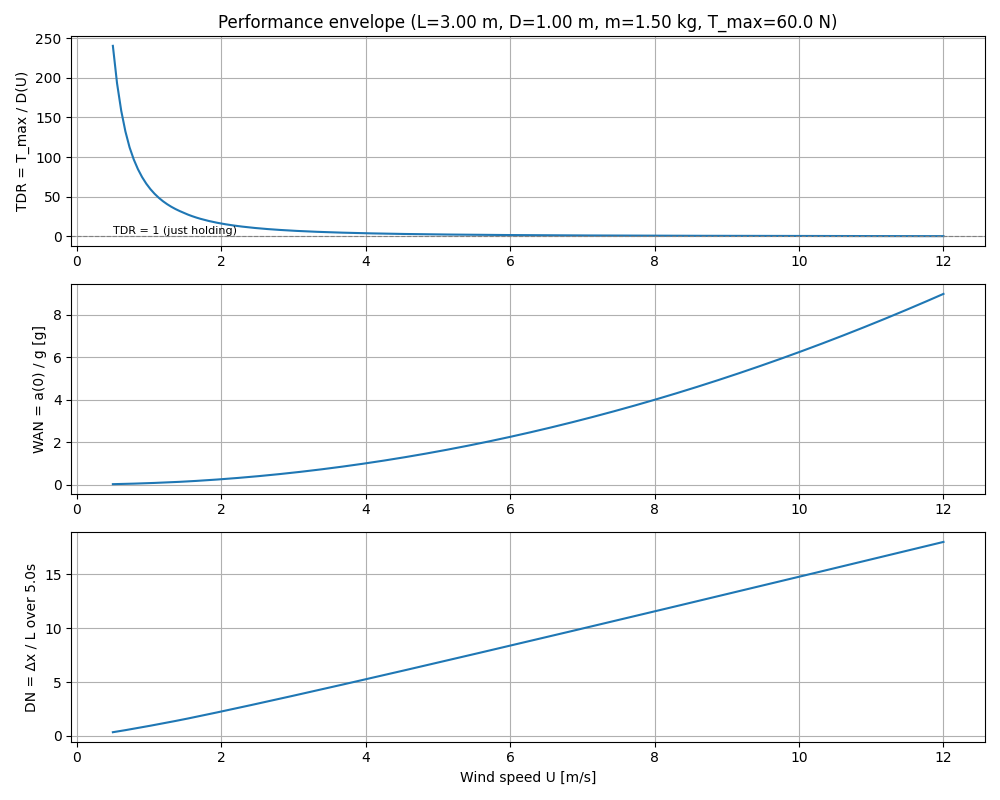

Lastly we want to see if we still have the ability to keep station, or even make headway against a gust of wind. For that, we again assume the pathological/least-efficient case of a broadside gust, using our motors to just push us sideways against the wind. We already know how to estimate a drag coefficient, so we can do a simple force balance between our maximum thrust available, and the drag as a function of wind speed. Call it the thrust-drag ratio:

TDR = T_max / D(u)

where:

T_max = maximum available thrust

D(u) = Drag force as a function of wind speed

Nice and conceptually simple. If TDR > 1, then we have enough power to overcome the wind. If TDR < 1, we will get pushed away, even at maximum thrust, and at TDR = 1 we’ll have exactly enough thrust to hold against the wind.

Performance envelope

So for a given combination of hull size, wind gust speed and duration, and vehicle mass, we can plot the performance envelope, which answers the operator’s fundamental question of “can I fly in this wind?”

It looks like this:

It was a pretty fun exercise to come up with these three ratios, and while I have never worked in lighter-than-air industry, I think they actually would add value in the design phase.